By Nick Willis

|

| Mount Kailas (click on any picture for larger image) |

“Kang Rinpoche…” The weary Tibetan mumbled as he pointed across the plains

to a snow capped range a kilometre or so ahead. The man was huddled in his

distinctive chuba, a long sleeved sheepskin coat and a clumsy fur hat that

looked as if it could have originated from Siberia. I was desperately cold and

being jolted across West Tibet in the back of a Chinese-made flatbed truck, one

of two foreigners amongst a throng of Tibetan pilgrims. I was semi-squatting,

unable to get my backside right on the vehicle floor, despite pushing and

re-arranging myself. My fellow passengers were making their journey for slightly

more religious reasons than me, and I watched them chatter and share dried yak

meat as we neared our destination.

The Tibetan plateau is a barren land rich in legends, myths and beliefs, many

of which stem from the fascinating and little known Bon religion. But

historically, Buddhism was the spiritual champion in the ancient kingdom, with

Tibetans following the words of the Lamas and ultimately the Dalai Lama, their

guiding spiritual leader.

Unfortunately, the mid-twentieth century dragged Tibet out of its reclusive

existence, in the shape of an armed invasion by The People’s Republic of China.

In turn, most would agree the entire fabric of Tibetan society has been diluted,

in an attempt to integrate the people with the Chinese motherland. The side

effects of this modernisation have been well documented elsewhere, and foreign

visitors will witness the Chinese grip on Tibetan affairs. However, visitors

will also note an almost unrivalled passion for the belief in Buddhism

throughout the land, despite the control of ruling communist China. This belief

is particularly evident in the remote and difficult to reach region of Western

Tibet, home of sacred Mt. Kailash, magnet to the waves of visiting pilgrims.

The holy Mt. Kailash, (Kang Rinpoche in Tibetan) is a beautiful unclimbed

peak, 6714 metres in height, to the Western end of the Gangdise Range. It’s a

politically sensitive area due to the nearby Nepalese and Indian borders, but it

hasn’t escaped the attention of Westerners. The mighty Reinhold Messner was

invited by Beijing to organise an expedition to climb the peak in the mid

1980’s, but decided not to press ahead when he realised the spiritual importance

of the mountain; “Of course I refused. It would not have been intelligent to do

otherwise”.

More recently, a Spanish expedition was organised in 2001 by Jesus Martinez

Novas. International dismay was massive, amongst critics was British climber

Doug Scott, in hoping they would think their actions through; “How will they

feel later in life about diminishing this mountain?” Messner also spoke out

again in defence of the peak; “Once that sanctity is destroyed, it will be gone

forever…I would suggest they go and climb something a little harder. Kailash

is not so high and not so hard.” A great put down with regard to the climb if

nothing else! The Spanish team fortunately quit their plans before reaching the

region. The Indian Government has since persuaded Beijing to agree that no

climbing permits will be granted in future.

Time will tell…

How can a mountain be so important? It’s spiritual importance dates back to

the Bon and Hindu religions, but it’s legendary four faces of lapis lazuli,

ruby, gold and crystal, today primarily attracts Buddhists who circumambulate

the supposed home of the Buddhist saint Milarepa in a clockwise direction (Known

as a Kora). The peak is described as the earthly manifestation of mythic Mount

Meru, the centre of the universe in Hindu, Buddhist and Jain cosmology. Hence,

all across Tibet, people will describe Kailash as the ‘navel of the world’, or

the ‘precious jewel of snow’. Its situation, towering above the nearby plains is

definitely striking. On paper, it’s not as high as peaks in the nearby Himalaya,

but its outlook is unspoilt as it dominates the surrounding range.

Tibetans take their spiritual worth seriously, so it’s probably for the best

that mountaineers have passed up the challenge thus far; Disturbing Buddhist

saints on the navel of the world shouldn’t be considered lightly. But of course

there’s no problem in joining the pilgrims and trekking around the mountain.

This was my aim and the reason for a 2100km journey from Lhasa to the Kailash

region.

It had taken me eight days and hitching on five different vehicles to reach

the area, incredibly frustrating at times. I watched endless trucks drive right

past me whilst I stood in blizzard conditions. The trucks communally used by the

pilgrims seemed to be the best option for stopping, clearly the most

compassionate! I also got involved in a very heated ‘discussion’ with a Kazakh

driver who demanded more money part way through a journey. I guessed he wasn’t

making a great deal driving through these parts of Central Asia and I had a big

rucksack, I must have appeared wealthy. It is possible to take the relative

comfort of a Toyota Landcruiser from Lhasa, but at a price. I was travelling

independently to further my meagre wallet, but this in itself is illegal in West

Tibet. I had to pay a small fine in the provincial capital, Ali, 200km from Mt.

Kailash. This enabled me to travel in the region for an unhindered 14 days.

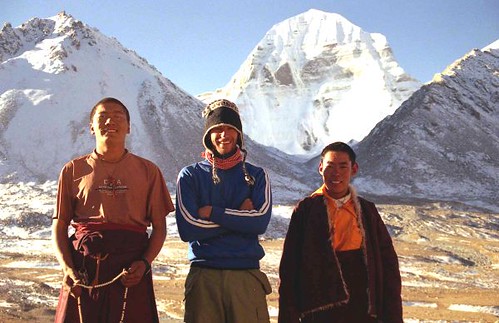

|

| Nick and monks |

Difficulties aside, I found myself in Darchen, ready to set off on a trek

around Mt. Kailash. Plenty of pilgrims were camped around me, also preparing for

the off, whilst market stalls sold stale Chinese chocolate, fizzy green tea and

instant noodles as provisions for the kora. Actually, I had hoped for some food

with a little more substance. Some entrepreneurial Tibetans were hiring yaks out

to groups as baggage carriers. I set off at first light, travelling as light as

I could; The starting point altitude was a heady 4560m, and the first days walk

would see me gaining a further 200m in altitude. Despite being mid October,

apparently the end of the pilgrimage season, there were plenty of Tibetan folks

also setting off. Entire families were jostling along the alpine meadow, placing

stones at cairns and stopping occasionally for the obligatory yak butter tea

breaks.

|

| Pilgrim Kids |

Now, for the first time, I was seeing the devotion the people have for this

area. The ultimate kora for dedicated Tibetans is a circuit of the mountain

whilst making full prostrations. This involves lying face down on the ground,

arms outstretched in prayer, then standing, moving forward one step and

repeating the process. This is unbelievable, all the more incredible when I

realised the kora is 52km in length. It would take me two and a half days, but

for those prostrating the full distance, allow approximately three weeks!

Needless to say, very few Western folk attempt this style of Kora.

Throughout the first day, I was aware of a dull headache, but as I neared the

small isolated monastery, which would serve as my room for the night, the pain

became intense. A rising sickness was taking any pleasure out of the last few

kilometres that day and I struggled to climb the steps up to Dira Puk Gompa, the

monastery in question. The two resident monks welcomed me into the

kitchen/living space, dominated by a yak-dung burning stove, invariably the

centre of any Tibetan building. I immediately lay down, overcome by nausea,

dizziness and confusion. This was the second time I’d experienced altitude

sickness and it was an unnerving feeling, barely able to lift my head from a

pillow.

Fortunately, a Japanese trekker was also stopping over in the monastery.

Rather more organised than myself, he had cunningly brought some altitude

medication ‘Diamox’ which I proceeded to scoff with as much water as I could

drink. Whilst lazing near the warm stove, one of the monks explained that he

studied Tibetan medicine and proceeded to hold my head between his hands,

promising me this would ease the pain. I wasn’t quite sure of the reasoning

behind the technique, and ten minutes later he stopped and continued sipping his

tea, seemingly oblivious to my pain. My head was still pounding and I was glad

I’d already taken the Diamox; I’m a true believer in pharmaceutical

medicine.

A restless night led to a clear cold dawn and a direct view of the North

(Gold) face of Mt. Kailash from my window, at the top of the monastery. A photo

of the Dalai Lama (Whose image is banned by the Chinese) had helped me secure

the best space directly above the only heated room, the kitchen/living area.

Interestingly, my room doubled as a studio for the arty monks who worked on

Thangkas (Tibetan Buddhist paintings) for the region, though some of the fierce

deities painted on the wall were a little haunting. I blamed the altitude

sickness.

After Tsampa breakfast and a farewell to the monks, my head was clearing and

I set off across moraine from the Kangkyam glacier, running down from the North

face of Kailash. The target for the day was the 5630m Drolma-La Pass, and it was

upwards all the way. There were still friendly Tibetans to point the direction

if ever I was unsure, though unusual markers helped reassure me; Shiva-tsal is a

kind of viewpoint where pilgrims are meant to suffer a symbolic death. Each

person would take an item of clothing off and leave it draped across one of the

many cairns dotted around the snow-covered ground. All around me was tattered

clothing left to the frozen jumble site, each item representing a life the

Tibetans had left behind.

|

| Steps in the Snow |

I followed the steep ascent trail east over ice, snow and rock, slipping

occasionally, whilst listening to the chanting around me intensifying; ‘om mani

padme hum’ the oft repeated mantra of the Tibetan people. I felt much stronger

than the previous day and defiantly plodded ever upwards. At 5630m I thankfully

reached the Drolma-La Pass under clear sky and relatively warm sunshine. I was

greeted by a small crowd of Tibetans throwing Tsampa in the air and adding to

the largest mass of prayer flags I’d yet seen. I stomped through the fresh snow

to get some photos and enjoy views across the land of snows, although the

partying pilgrims reminded me I wasn’t alone. Unfortunately, Kailash itself is

not visible from this pass, so it’s impossible to see if the Gods really do

reside at the top. To the South East was my descent route past Lake Gouri Kund,

then another 28km and a day and a half of walking until my Kailash Kora would be

complete. But more importantly, a lifetime of sins would then be wiped away,

according to Tibetan Buddhist belief.